In 2019, Public Health England stated that gay and bisexual men, Black Africans and people born abroad are the three key population groups disproportionately at risk of HIV.32 This information helps to determine targeted interventions to reduce the burden felt by particular groups . Within these groups, sub populations are more at risk . While all groups experienced a decline in diagnoses between 2018 and 2019, there was a 14% increase in Black African gay and bisexual men, and a 44% increase in Black Caribbean gay and bisexual men between 2017 and 2018. For heterosexuals, the pattern reverses: there has been less progress for white heterosexuals compared with Black African and Caribbean heterosexuals.

We heard from many stakeholders who emphasised the need to think about intersectionality in our work . We know that often gender, race, sexuality and country of origin interact and that considering sub populations and emerging groups is essential if we are to prevent new transmissions . We also know that there has been little recent progress in reducing diagnoses in women from Black African, Black Caribbean, Black other and mixed/other ethnicity group, for example. People of Latin American and West African ethnic origin represent two of those key populations where progress seen for other groups has not been replicated . We heard from minority led groups who told us that too often, the differences within populations is not reflected in services and interventions.

In our targets for ending new transmissions, we are clear that progress must be equal across population groups and regions. By 2025, we must have reduced new HIV transmissions by 80%, which would mean 900 new transmissions across England . Our target data table breaks down these target population groups, so that progress can be measured not just on a fall in new diagnoses overall, but within groups. Without this, we will ultimately not be able to end new HIV transmissions in England.

Women

Women make up a third of people living with HIV, with an estimated 31,000 women living with HIV in the UK . As a group, women do not experience the best HIV outcomes: 52% of women diagnosed in England in 2019 for the first time were diagnosed with HIV late (above the average of 48%) and women are not experiencing the same rates of decrease in new diagnoses as other populations . With this in mind, it is not a surprise that women often feel invisible in the response to HIV in the UK, reporting they feel ignored or not taken seriously by healthcare staff and researchers .33 Of the missed opportunities to test for HIV in sexual health clinics in England, 75% were women; women are both less likely than men to be offered a test, and less likely to accept one when offered .34 This contributes to the fact that women are more likely to get their diagnosis at the GPs, antenatal clinics or at other hospital outpatient departments . We both need to be reaching more women with tests in sexual health clinics and in other preferred settings.

The demographic of women with HIV has broadened in recent years . Fewer HIV diagnoses are made in Black African women (although they still make up 34% of new HIV diagnoses), and new diagnoses are increasingly likely to be UK-born, white or another minority ethnicity and aged 50 or older. Currently in the UK, 4 out of every 5 women living with diagnosed HIV are migrants and 3 in 4 are from minority ethnic communities . There is little knowledge or research to understand who women at risk of HIV are . This holds back interventions targeted at a key population in the HIV response.

The way women’s sexual and reproductive health interacts is often neglected in the HIV response . For example, women living with HIV continue to experience high levels of menopausal symptoms, which often go under-managed and therefore impact their quality of life and engagement in care.35 Instances where women access sexual health services represent an opportunity for an increase in HIV testing of women, while also addressing misconceptions about who is affected by HIV.

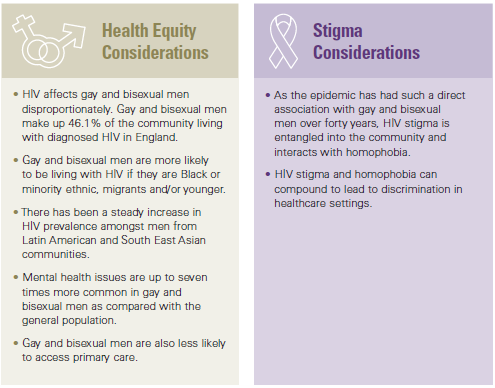

Gay and bisexual men

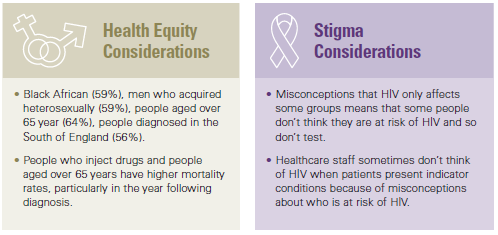

Since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, gay and bisexual men in England have been disproportionally impacted by HIV . The community makes up an estimated 2 .6% of the UK population but 47 .8% of all people living with HIV, making gay and bisexual men the group most at risk of HIV acquisition in the UK . This association has impacted generations of gay and bisexual men’s relationship to sex and identity . Further, the historical and current interaction of HIV stigma and homophobia has led to entrenched misconceptions that only gay and bisexual men are at risk of HIV.

Although overall gay and bisexual men have seen the most progress in falling new diagnoses rates, this has not been distributed evenly across subpopulations within the community . Black (both African and African Caribbean) gay and bisexual men remain disproportionately affected by HIV. For Latin American and South East Asian gay and bisexual men, there has been an increase in HIV prevalence over recent years . Young men have also not experienced a decrease in new HIV diagnosis . Trans and bisexual men have often been left out of these prevention messages . Therefore, we must remember both that the burden of HIV remains high for all gay and bisexual men and that this is not a homogeneous group . Targeted interventions have meant a significant overall reduction in transmission, but still some are not part of these successes.

Gay and bisexual men are not only disproportionately affected by HIV but overall, by poor sexual health and STIs . In particular, there has been a rise in syphilis and gonorrhoea in this group . There has also in the past 15 years been a significant increase in chemsex across all groups of gay and bisexual men, and a recent study suggested HIV positive men living in the UK reported higher levels of chemsex compared with three other European countries .36 Running parallel to this trend, other changes in gay culture such as the closure of LGBT spaces has led to reduced opportunities to interact with gay and bisexual men and disseminate information in traditional ways. We don’t fully understand the impact of apps like Grindr and social media on these patterns, but they have created different ways for men to engage and meet for sex which has undoubtedly changed things. This presents both challenges and opportunities for health promoters to engage and disseminate prevention messages.

In addition to sexual health, there are distinct but overlapping areas in which gay and bisexual men bear a disproportionate burden of ill health: particularly in mental health, in the use of alcohol, drugs and tobacco and experiencing discrimination in healthcare.

Debates around whether to name this population group based on behaviour or identity (‘men who have sex with men’ (MSM) or ‘gay and bisexual men’ (GBM) are ongoing . Some men who have sex with men do not identify as gay or bisexual and do not engage with LGBT+ services . They, therefore, may be less informed about prevention and support but still at risk of HIV . However, many gay and bisexual men feel that the acronym ‘MSM’ medicalises their identity or perpetuates self-stigma and shame . In 2018, Public Health England’s annual report on HIV in the UK used the term Gay and Bisexual Men to identify this group for the first time.

Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities

The term BAME is used as an umbrella term to encompass diverse, complex communities . It often obscures the specific health needs of groups which are not homogeneous . BAME communities are overall more likely to be living with HIV, and particularly Black African communities are disproportionately affected by HIV . Black Africans are identified by Public Health England as a key population living with HIV, with 38 per 1000 living with HIV. Gender plays a big role too, with Black African women nearly twice as likely as Black African men to be living with HIV, with a prevalence of 51 per 1000, compared with 26 per 1000.

BAME people are not only more likely to be living with HIV but are more likely to be diagnosed late, with accompanying consequences for health . Black African (59%), Black Caribbean (48%), Black other (47%), Asian (46%), Other / mixed (40%) the next ethnic groups most likely to be diagnosed late . Since 2015, rates of late diagnosis amongst Black African heterosexual men have been rising, from 59% to 69% in 2017 . Some ethnic groups are not effectively captured by the data collected by GPs and sexual health clinics, which has implications for reports, funding and research opportunities.

For example, groups categorised as ‘mixed/other’ include many ethnic groups with different needs, for example Latin Americans and various groups from the Middle East . This ‘mixed/other’ group makes up 11% of those diagnosed with HIV in 2019 in England, the next largest group after white people (57 .4%) and Black African (19 .2%) . While the ‘mixed/other’ group is the least likely to be diagnosed late (40%) this may hide trends in subpopulations that are not identifiable in the current surveillance data . Although country of birth is recorded, this is not sufficient for identifying the risk factors of second and third generation migrants.

Alongside the severe health inequalities experienced by Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities, there are multiple barriers to accessing appropriate services . This can include language, cultural barriers, stigma, homophobia and heteronormativity . As a consequence, BAME people living with HIV often feel less informed about their condition . This is exacerbated by the context of hostile environment policies and the Windrush scandal, which make many BAME people reluctant to access services . Despite knowledge of the disproportionate effect of HIV on BAME communities old mistakes were repeated in recruitment for the PrEP trial and uptake among BAME communities has been very low . When routine commissioning is introduced, this means concerted effort must be made to remedy this inequality . We know what works: community-led responses are most effective in creating changes, and there is a need to recognise the expertise and leadership of BAME individuals and organisations in any strategies and plans to prevent new HIV transmissions within BAME communities.

Young people

The cohort of young people (under 25s) living with HIV in the UK is among the most marginalised of groups of people living with HIV . This group includes children who acquired HIV through vertical transmission (at birth and through breast feeding) and adolescents who acquired HIV through sex .

One of the biggest success stories of HIV in England is the tiny rate of vertical transmission from diagnosed women in the UK (less than 0 .3% of those who become pregnant) . This is in part the result of routine antenatal screening, which identifies undiagnosed HIV in pregnant women . This means that pregnant mothers living with HIV can quickly initiate antiretroviral therapy, which prevents transmission . Testing for HIV in antenatal services is opt-out, which makes HIV testing feel like a regular part of a pregnancy health check .

We have much to learn from the success of this policy . Since 2012, there have been decreases in recorded new diagnoses of HIV amongst under 15s, with 15 new diagnoses in this age group in 2019 . In the age category of 15-24, there has been a fall in new diagnoses since 2015, but still 294 children and young adults between 15 to 24 years were diagnosed in England in 2019 . In the UK, 20% of young people living with HIV are currently not virally suppressed .39

The transition from paediatrics to adult clinics at 18 is not always a smooth one for young people living with HIV and some drop out of care altogether . In the UK there is a large gap in services, and young people report feeling that services do not feel tailored to their needs .40 Children leave behind a multidisciplinary team who have worked them for an average of 11 years and lose much of the holistic support they received as an under 18, including psychosocial support . This stage of adolescence is recognised as a critical period for developing self-management skills and building the foundations for good health in adulthood . Outcomes for long-term conditions are not as good in adolescents as in children and adults, which could be linked to the poorly planned transition from paediatric to adult care .41 Often stigma leads young people to go to their HIV Consultant for other health needs so as to not have to share their HIV status with other healthcare professions . When new to adult HIV services, this can lead to further health inequalities as minor health problems are not resolved.

Another critical factor for this cohort is education: both for prevention and challenging stigma . Children and young people living with HIV and at risk of HIV need to be informed about what HIV is and the treatment and prevention available . Young people living with HIV need the skills to negotiate health, relationships and sex as part of their development . They also need their peers to have this knowledge and awareness, so they do not have the burden of educating others to prevent stigma . For young people at risk of HIV, particularly young gay and bisexual men, who often are not informed of HIV prevention methods at school, this is compounded by experiences of potential marginalisation and prejudice from peers, family or community .

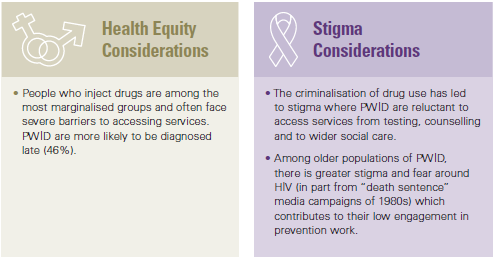

People who inject drugs

HIV prevalence amongst people who inject drugs (PWID) in the UK remains low (1 .2%), but estimates suggest that the risk of contracting HIV for this group is 22 times greater than for people who do not inject drugs . This group is susceptible to focused outbreaks, and this is currently ongoing in Glasgow and South West England . We also know that prevalence could be higher than the data we have, because, for example, a new HIV diagnosis in a gay man involved in chemsex tends to be recorded as a ‘men who have sex with men’ diagnosis . While the needs of those involved in chemsex may be different to other drug users, both need to be addressed in all their nuance if we are to end new HIV transmissions .44

Chemsex is particularly relevant in the country’s HIV response . While the number of people injecting drugs before or during planned sexual activity is very low, they are at a very high risk of transmission of HIV, hepatitis B and C and other STIs . While historically chemsex has been associated with gay and bisexual men use, there is an emerging anecdotal evidence suggesting that increasingly chemsex goes beyond gay and bisexual men.

We have seen that successful stories come from places with greater collaboration between sexual health and drug and alcohol services (including chemsex) . They look into addressing the complex needs of individuals (for example, homelessness, poor mental health and poverty) and making engaging with support services easier to them . However, significant cuts to drug treatment services (by 26% since 2014/15) alongside cuts to sexual health budgets have affected the ability to form these partnerships . The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs reported that reductions in local funding are the single biggest threat to drug misuse treatment recovery outcomes being achieved in local areas.

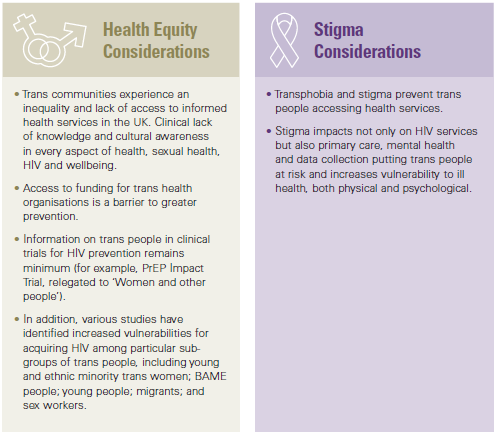

Trans communities

Literature on trans people and HIV is full of gaps and “more research is needed” text, but among available studies, we know there is a high HIV prevalence in the trans community with a heavy burden of HIV on trans women .45 Trans people in England face social exclusion, economic vulnerability, and are at an increased risk of experiencing violence . Systematic disempowerment of the community has had a direct impact on their sexual health, in particular around negotiating safer sex practices.

There was a long history of no national data on trans people living with HIV since the beginning of the epidemic . This started to finally change in 2015 when new HIV diagnoses cases among trans people started to be recorded . The impact of HIV among trans people in England before 2015 remains widely unknown . In 2017, a new code to record trans people attendance to sexual health services was introduced . The commission learnt that the use of this code is yet to be fully implemented. All this makes it harder to fully understand the impact of HIV among trans people and how to best address their needs.

We learnt from community members that prejudice and transphobia remains present in some healthcare settings, in particular in those outside sexual health . Trans people are far more likely than the general population to report worse mental health and wellbeing, which combined with prejudice faced in healthcare settings, can impact HIV treatment and prevention .46

Trans led organisations have been effective at engaging with trans people . They have been successful at using holistic and asset-based approaches to the health and wellbeing of the community . As such, community-led efforts should be at the centre of decision making and programme delivery of HIV interventions addressing the needs of the trans community . Without organisations like cliniQ trans take up of the PrEP IMPACT Trial would have been very different – this should be considered with the roll out of routine commissioning of PrEP.

“If we are to reach the 2030 target, no group or geographical area can be left behind. It will be vital that epidemiological data is analysed to a granular level to unpick where inequity in progress to reduce HIV rates (and deaths) is occurring.”

Terrence Higgins Trust

Meeting the equality challenge with the right data

Greater nuance must become more than a part of our approaches going forward. In Bristol, we were told that the acronym ‘BAME’ risks becoming meaningless as a catch all term for a diverse group of people . We agree that we need to be more specific in our understanding and the language we use when addressing inequalities experienced by different communities of colour in England .47 We heard there has been little progress in ethnic groups categorised as ‘mixed/other’ and this category is not fit for purpose . We urgently need a clearer understanding of those most affected by HIV in this group to prevent inequalities being perpetuated . We recommend that data collection systems are updated to reflect this, including options to record Latin Americans and people from the Middle East . Without this clearer information, we are unable to target interventions towards these groups . Unhelpful generalisations are also used in data collected about women living with HIV in England. Current data collections record all women as heterosexual, meaning that there could be a significant amount of data missing on bisexual and lesbian women .48 At the very least, data and research should use known route of transmissions rather than assuming all women living with HIV are heterosexual .49

Most importantly, over the next 10 years that system must be able to respond to even small changes in the data in order to effectively tackle HIV . We cannot stop at having better data . We must use this better data to inform our approach to ending new transmissions . Communities are not ‘hard to reach’, we just need to adapt our tools to better reach them .50

“The inclusion of the ‘Latin American’ community in the surveillance system is crucial if we want to tackle the poor health outcomes among this community. Local Authorities need to collect and report data on the special health needs of the Latin Americans.”

Coalition of Latin Americans in the UK

Late diagnoses

To end new HIV transmissions by 2030, we must end the cycle of late diagnosis . Since 2015, there has been no improvement in the percentage of people diagnosed late in England . Between 2016 and 2019, the percentage of all newly diagnosed who were diagnosed late has fluctuated around the high 40%s .51 Certain groups are more likely to be diagnosed late, for example 59% of heterosexual men diagnosed in 2019 were late diagnoses . The number of late diagnoses is not the perfect indicator of how good the system is at finding a new case of HIV, because a rise in late diagnoses could represent a short-term improvement in finding those undiagnosed . There are currently an estimated 5,900 people living in England with an undiagnosed HIV infection and it is imperative that they are tested and diagnosed .52

However, in the long term, these levels represent a failure of the system . That’s why we think every person in England should know their HIV status . We were shocked how a lack of awareness of the risk of HIV, particularly among healthcare professionals, can put people unaware they are living with HIV in dangerous situations. For example, the belief that a heterosexual woman could not have HIV, despite presenting symptoms, had life-threatening consequences for an evidence hearing attendee.53

“I did not think HIV was a risk for me … nor did my GP. So HIV testing was never really thought about until I was ill and in hospital.”

Ben Cromarty

A person living with HIV is considered to have been diagnosed late if they test positive for HIV after the virus has already started to damage their immune system (when they have a CD4 count below 350) . Being diagnosed late increases the risk of dying by eight-fold and it is estimated that someone who is diagnosed very late with HIV has a life expectancy at least 10 years shorter than someone who starts treatment earlier . It is also likely that people diagnosed late have been living with an undiagnosed infection (for three to five years) and so may have been at risk of passing on HIV to partners . In 2019, 48% of adults diagnosed in England were diagnosed at a late stage of HIV infection, a shocking level which requires urgent action. The best way to address late diagnoses is through increased HIV testing . The sooner a person knows their HIV status, the better chance they have of improving their health and accessing HIV treatment if needed.

However, this also represents an additional challenge . As increased testing leads to more people being diagnosed during the very early stages of infection, the definition of late diagnosis (as having a CD4 count below 350) may misclassify people diagnosed who seroconverted recentlyas during this period when immune systems have recently started fighting the HIV virus, CD4 counts can be lower . This could be addressed by close monitoring and investigation of each late diagnosis reported in the country. This approach would also allow us to better understand missing opportunities to identify cases earlier.

Learning from failure

Our plan includes actions that should prevent late diagnoses; in particular, training all healthcare staff and making opt-out HIV testing routine across the health system . Alongside this, we need to change the way we approach a late diagnosis . In evidence submissions and at public hearings, we heard that the best way to do this is to treat each late diagnosis in England as a system failure and follow it with a serious incident investigation.54 We recommend that this is the case.