Stigma and health inequalities create significant barriers to accessing testing, prevention, and care . This has become more acute since COVID-19 and without action, we risk progress slipping further . Everyone involved in the health and social care sector has a responsibility to stop HIV stigma and address health inequalities throughout their work.

There is an urgent need to end stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV . This will not be a simple process and requires that the law and government policy properly protect against discrimination and does not perpetuate stigma . This must be done while changing public attitudes in order to end stigma .3 Submissions received emphasised that better knowledge about HIV can help to challenge associations of HIV with contagion and death but cannot alone eradicate HIV stigma . Stigma remains deeply bound up in other discriminations, with racism, xenophobia, transphobia, sexism and homophobia all playing key roles in continued stigma and misconceptions about people who live with HIV .

This hampers attempts to get people to come forward for testing and means too often those living with HIV are diagnosed late and risk complications . It stops dialogue about HIV in families, health settings and communities that could otherwise educate people about the modern realities of HIV and its treatment options. With the right medication, HIV is life changing not life threatening – this is often poorly understood among healthcare professionals and the public alike . Despite the fact that people living with HIV are protected by the Equality Act 2010, people living with HIV face discrimination in employment, access to services and often in their personal lives.

“Addressing stigma is not just ‘zero stigma’ as this definition only depicts something we don’t want. Zero stigma may mean that people with HIV are just tolerated rather than fully accepted, respected, and included.”

Positively UK

The COVID-19 crisis has held up a mirror to a reality that the HIV sector has long known: that structural inequalities have serious implications for public health . From its beginning, the HIV epidemic has represented an acute health inequality, affecting some key populations vastly disproportionately . In addition, recent declines in estimated HIV transmissions have not been spread equally amongst all key population groups or across regions .4 For example, while the most significant drop has been amongst white gay and bisexual men living in London, aged 25 to 49, increasing numbers of gay and bisexual men born abroad are more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than those born in the UK .5

That structural inequalities influence health outcomes is well evidenced . The 2010 Marmot Review into health inequalities in England found that the lower someone’s social and economic status, the poorer their health is likely to be.6 The review exposed that people living in poorer areas in England will die seven years earlier than people living in the richest neighbourhoods and will spend more of their lives with a disability . The review also confirmed that health inequalities are preventable and reiterated the economic case for prevention rather than treatment . Marmot also argued that action on these inequalities not only requires action on health, but on determinants of health: education, occupation, income, home and community . Returning to these findings 10 years later, Marmot found that life expectancy had fallen for women in the most deprived communities outside London, and in some regions also for men . The rate of slowdown has been the greatest in England for 120 years. The findings of these reviews were warnings for what was to come .7

COVID-19 has further increased many of these health inequalities. In June 2020, a UNAIDS report noted the effects of COVID-19 on the HIV response as three-fold: there has been a shift in the attention of healthcare systems towards COVID-19, the health challenges of people living with HIV have been exacerbated and system level weakness in the epidemic response has been highlighted .8 COVID-19 has disproportionately affected many of the marginalised groups most affected by HIV . Particularly, data published by Public Health England in June 2020 showed that BAME communities in particular were more likely to die of COVID-19 .9 10 A key theme highlighted by this work on COVID-19 is also true of the HIV response: action on inequalities must be data led . If our data is not robust, it holds back the progress that can be made in addressing inequalities . Solving these structural inequalities goes beyond HIV and is not only the work of this commission, but it is nonetheless vital that tackling them underpins every part of our work.

Stigma, discrimination and health inequalities hold back our efforts to end new HIV transmissions at every stage . All policies and future practice should be assessed to determine whether they do not further stigmatise HIV diagnosis, perpetuate discrimination and exacerbate health inequalities .

All national and local HIV treatment and prevention initiatives should explicitly plan and evaluate how they will address HIV-related stigma, discrimination and health inequalities .

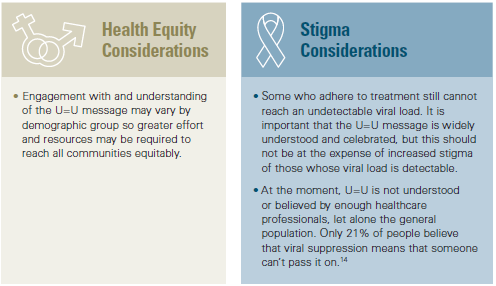

Alongside this, we must increase the knowledge and awareness of HIV amongst the general healthcare workforce . Too often we heard accounts of stigma experienced within the healthcare system, including nurses ‘double-gloving’ and multiple accounts of appointments being moved to the end of the day so rooms could be ‘decontaminated’ . This exposes a serious problem in the level of knowledge among some healthcare staff who don’t know or believe that a person with an undetectable viral load cannot transmit HIV – this is known as undetectable = untransmittable or U=U . This perpetuates stigma and leaves people living with HIV deterred from engaging with care . Not only this, but it is symptomatic of other problems: that many healthcare staff are not aware of indicators of HIV and believe that it only affects certain minority groups. This can lead to patients being seriously ill before they are tested for HIV.

“Patients often report trauma as a result of needing ICU care before HIV testing is considered. Further trauma is reported on diagnosis when

they are left bewildered and unsupported by staff who are unaware of new treatments and services available and may be insensitive to the

confidentiality requirements of newly diagnosed HIV+ patients.”

Mary

People living with HIV often experience stigma within the healthcare system itself, which acts as a barrier to people living with HIV accessing services . This stigma also indicates that not all of the health and social care workforce has sufficient up-to-date knowledge of HIV, which can also mean that HIV indicator conditions go unnoticed.

As more people living with HIV access non-specialised healthcare, training on HIV and sexual health should be mandatory for the entire healthcare workforce to address HIV stigma and improve knowledge of indicator conditions.

Public awareness campaigns

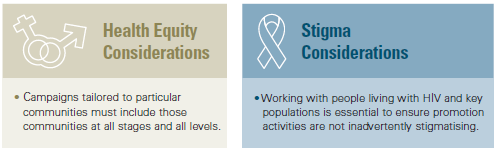

England has a long history of using social marketing campaigns to increase knowledge and awareness of HIV . From the 1986 “Don’t Die of Ignorance” campaign to recent efforts targeting most at-risk populations, such as Black African communities and gay and bisexual men. In England, the commissioning of campaigns has been carried out by multiple sectors and has proved to be effective at increasing and normalising HIV testing and condom use, reducing HIV stigma and providing the latest up-to-date information on HIV . The return of investment on campaigns can be variable among populations and there is always a risk of enhancing stigma among communities if campaigns are generally targeted, rather than more carefully tailored towards communities . Campaigns which increase fear and stigma in their messaging are counterproductive in encouraging people to test and talk about HIV, impacting the quality of life for people living with HIV . Instead, campaigns must be tailored to communities in a way which informs and supports, without isolating specific populations.

At evidence hearings, we heard that there is a tension in current campaign messages. On the one hand, we encourage people to access prevention so as not to acquire HIV, while also highlighting that improved treatment means HIV need not affect your life and health but does reduce radically – potentially to zero – someone’s ability to pass on the virus . Both are relevant messages, which need to be carefully propagated to ensure they complement each other as part of a combination HIV prevention strategy . Effective campaigns require simple messages, and we know combination HIV prevention can be inherently complex to explain.

Campaigns have been one of the places where we have seen successful early development and adaptation of new technologies . The use of digital approaches in social marketing has dramatically changed the way campaigns are formulated . They are now able to ‘hyper target’ communities with different messaging becoming an invaluable tool to influence and impact population health at scale.

Treatment as prevention and U=U

The discovery11 that people living with HIV who have an undetectable viral load cannot pass HIV on through sexual transmission was a game-changer in the fight against HIV. In 2015, NHS England introduced a policy known as ‘Treatment as Prevention’ which enabled doctors to prescribe HIV medication to people living with HIV before it was otherwise clinically indicated, to prevent onward transmission .12 Evidence from the START Trial then demonstrated that those who begin HIV medication as soon as possible after diagnosis have better health outcomes – which further changed prescribing practice in England.

This understanding is known internationally as undetectable = untransmittable or U=U .

In the UK, 89% of people living with HIV have an undetectable viral load . Of those receiving treatment, 97% have an undetectable viral load . U=U makes the reasons for providing good treatment two-fold: it enables people living with HIV to lead healthy lives and means that they cannot pass on HIV . The U=U message is widely shared by HIV activists internationally, including through Terrence Higgins Trust‘s very successful ‘Can’t Pass It On’ campaign . It enhances motivation for adherence to antiretrovirals, mitigates anxieties around HIV testing and challenges some instances of stigma that relate to fear of transmission . U=U also assures people with HIV that they can conceive naturally, without risk to their infant and have sex without fear of passing on the virus to their partner . Anecdotal evidence suggests that the message is broadly welcomed by people living with HIV and there is some community frustration that the wider public are not better informed on this significant progress . Although there have been small incremental changes in public understanding of U=U, recognition of the message remains low.

U=U messaging refers to sexual transmission . The evidence for the U=U messaging on breastfeeding and other exposure routes (including sharing needles) is still evolving . A roadmap for global collaborative research exists in order to enable those who want to breastfeed to make a fully informed decision .13